2010—onwards: Interview with Fabio Agostini

Photography by Pier Carthew

Models by Fabio Agositini

Styling by Stefanie Breschi

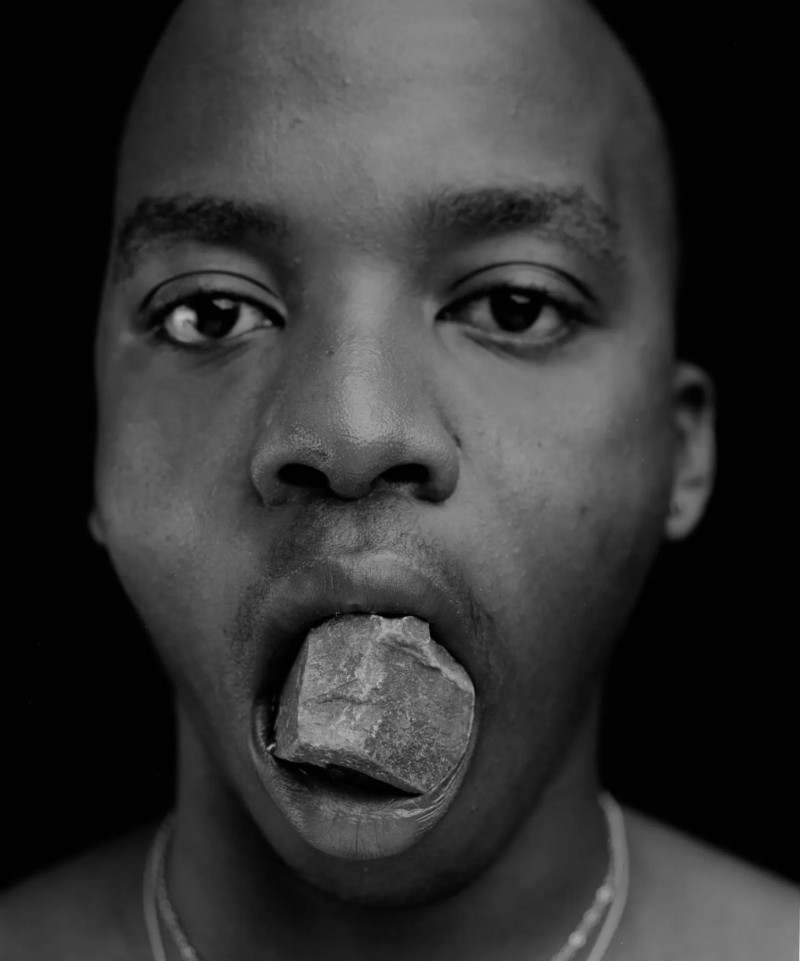

Melbourne-based architect Fabio Agostini has been working with concrete shapes since 2019. Beginning as a simple exploration of spatial configuration, his process has since gone on to explore works both abstract and figurative, mainly using and reinterpreting forms and symbols reflected in his past.

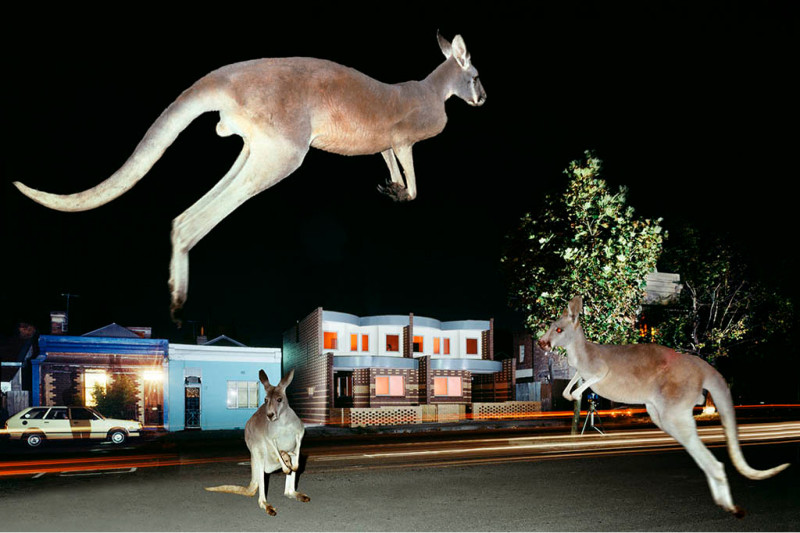

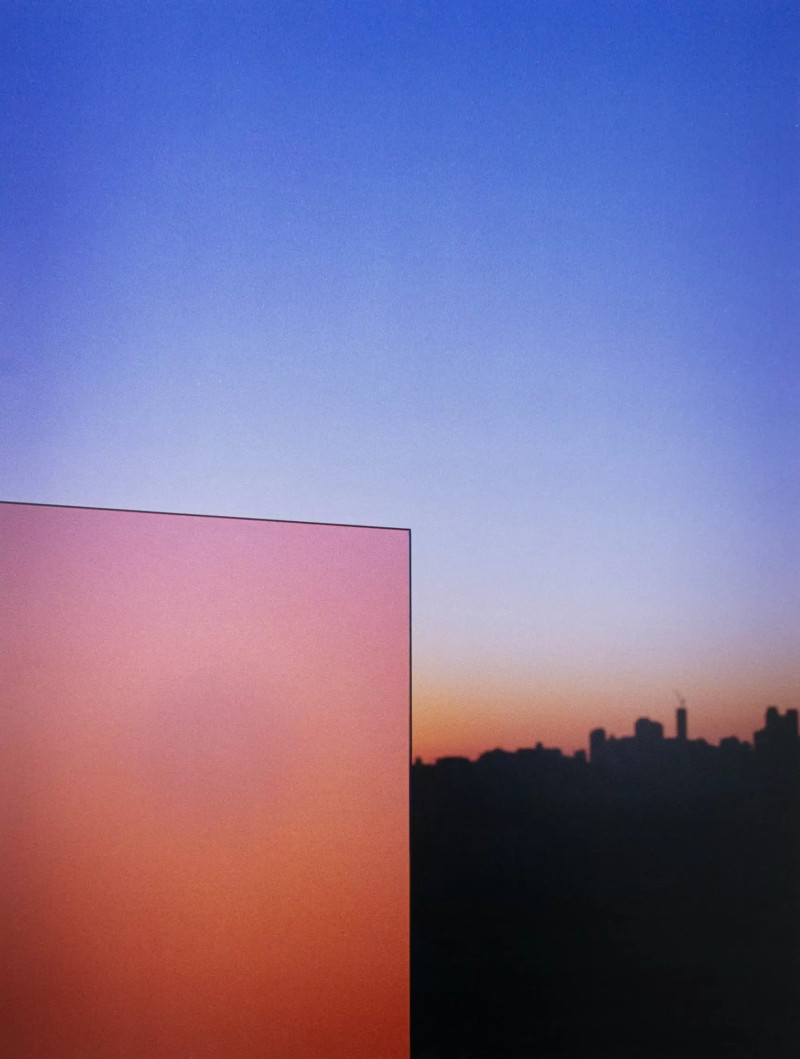

Hertford Street

231 Napier

Hello, what is your name, background and how did you end up doing what you do?

Fabio Agostini: My name is Fabio Agostini. I'm from Italy and I started making concrete sculptural objects to fulfil my need to build and create to fulfil my need to build and create.

I've always had this interest but I didn't do anything about it about it before coming to Australia. After the first year in this country, I had enough money and spare time to focus on things that bring me joy.

One day a colleague of mine showed me an article about concrete made artworks. It blew my mind. I never thought you could do something so graceful with such a coarse material that's usually associated with a much larger scale.

Then by chance, I saw on Instagram another sculptural object maker and it was like discovering a new universe of possibilities. I was amazed by how beautiful a simple textured shape could be. Once I finally made up my mind and decided to create my own artwork, I found the process similar to that of the models I used to make at university. I studied architecture in Florence and the concrete I make reminds me of the stones of that city.

What is your connection to the materials you work with, what do they do for you that others don’t?

FA: I chose concrete as my main medium because it's extremely democratic. It's cheap, simple to make, responsive to your inputs, and in a word—versatile. Most other materials like clay, wood, stone or metals require workshops to be worked in, they're usually messy and hard to find in small quantities.

Concrete gave me the opportunity to make artwork all by myself almost without any means. It's a kind of freedom that I learned to appreciate when I moved to a foreign country, far away from my home, my tools and my old network.

At the same time, I identified with the material itself. I felt we were both underdogs in a rag to riches story as concrete is made out of humble elements which, when mixed together with some hard work, become something stronger.

Fabio Agostini

Is there a recurring theme in your work?

FA: Archetypal elements are usually the lighting spark of my creative practice, maybe because only a simple idea can be visualised in a simple shape.

My interest in archetypes is due to their primordial strength as if they were a link to an older knowledge. The ones that I can relate to the most are in one way or another part of my past. There's a pool of ideas I'm fascinated by, from memories to what I studied, that doesn't change much over time. Sometimes I feel trapped in the past, a product and reproducer of a daggy and backward focused culture. I'd like to have fewer ties to the past, to be less 'passatista' (Italian: a person who stubbornly attaches themselves to the past) and be more innovative, but I can't complain as I do find a lot of inspiration in ancient cultures.

When you hear ‘trust the process’ what comes to mind?

FA: As a small practice, when I hear 'trust the process' it reminds me how painful the whole thing can be.

We live in a complex society based on hierarchy and the subdivision of roles. Trust the process means that even if you don't see the bigger picture, by doing your job you can keep the system working—and it works pretty well for structured business.

But when you do something the first time without someone instructing you or without knowing whether it's going to work, trust the process sounds completely different because there's no process at all. For example, in my making process, there's a gap between the design and the construction phase. It goes from the moment you stop setting things up to the moment the concrete gets poured into the mould. That's when you really have to trust your work up to that point because there's no room for change. It helps to have adequate knowledge of the subject, time to let ideas settle down, oblique thinking to see problems from different angles and passion to keep refining your skills.

If you could be reminded of something every day, what would it be?

FA: That Michelangelo completed The David by the age of 29 and Tupac wrote about 700 songs by the age of 25. Do something!

What else are you involved with that we might not know about?

FA: So, for a long time I have been mulling over an unacknowledged problem of our time: modern gravestones are uglier than the old ones (just like the pictures on them). Nowadays tombstones look more like kitchen islands than the shrines they're supposed to be.

It seems to be an odd paradox because as our societies became wealthier the quality of this particular item fell down.

I've been thinking about this for years and I have a few good designs in mind so, if anyone else out there agrees with my analysis and is keen to arrange a good looking home for their earthy rests, they can get in touch.

Fabio made 120 Campbell Street, (link: https://milieuproperty.com.au/spaces/hertford-street text: Hertford Street and 231 Napier for our exhibition 2010—onwards: A decade of creative development.

For more of Fabio's work follow Fabio on Instagram.

To stay connected with Melbourne Milieu, please follow us on Instagram.